Git worked for me long before I truly understood it.

So I built a tiny Git clone called lit - not to recreate Git feature-by-feature, but to understand why it behaves the way it does.

This post walks through how lit works internally and the mental models I built along the way.

Code:https://github.com/abel123code/lit.git

What `lit` supports

✅ `lit init`

✅ `lit hash-object -w <file>`

✅ `lit cat-file -p <hash>`

✅ `lit add <file | .>`

✅ `lit write-tree` (writes tree snapshot from the staging index)

✅ `lit commit-tree <treeHash> -m "message"`

✅ `lit log`

✅ `lit checkout <commitHash>` (restores working directory to that commit)

✅ `lit commit -m "message"`

Phase 1 - Repository initialization

Running lit init creates a .lit/ directory, which is Git's internal workspace.

.lit/

├── objects/ # all stored content (blobs, trees, commits)

├── refs/

│ └── heads/

│ └── main # branch pointer (stores latest commit hash)

├── index # staging area (path → blob hash)

└── HEAD # tells us which ref we are following

Key idea:

.lit/HEAD does not store a commit hash directly. It stores a pointer to a branch, e.g. ref: refs/heads/main. The branch file (refs/heads/main) then stores the actual commit hash.

Mental model:

HEAD ──► refs/heads/main ──► stores latest/current <commit-hash>

Phase 2 - Blobs (content-addressed storage)

Git stores file contents, not filenames. These are called blobs.

Commands implemented:

lit hash-object -w <file>: Allows you to take a file's content and store itlit cat-file -p <hash>: Given a hash, it will show you the text content

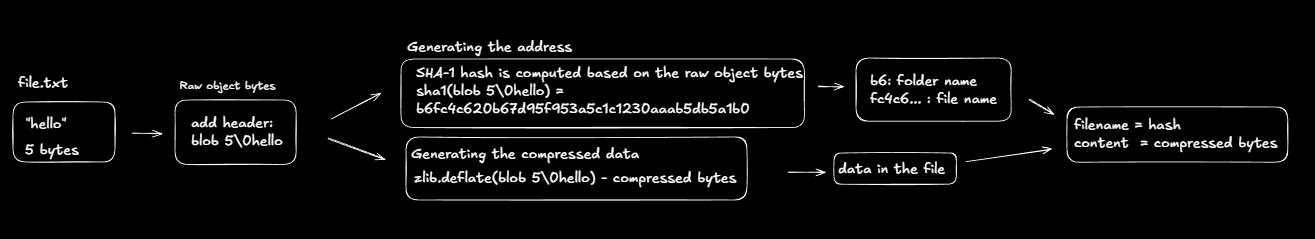

What happens internally:

- Read file bytes e.g 'hello'

- Add header: e.g blob <size>\0<content> → blob 5\0hello

- Compute SHA-1 hash of the raw bytes. This hash will become the address of where the blob will be stored e.g a 40 character hash is formed b6fc4c620b67d95f953...

- Compress with

zlib(think of this as compressing the content (blob5\0hello) so that it doesnt take up much storage) - Store at:

.lit/objects/<first-2-chars>/<remaining-38-chars>

.lit/objects/b6/fc4c620b67d9...

The hash is not just a label - it's a fingerprint. Same content → same hash → same blob. Git detects changes by comparing hashes, not files. This naturally deduplicates content.

Why Git uses 2 characters for folders

Lets assume that we wish to store 100,000 objects

Context: SHA-1 hashes are hexadecimal → 16 possible values per character.

SHA-1 is hex → 16 possible values per character.

- 1 char → 16 folders → too many files per folder

- 100,000 / 16 = 6250 files per folder

- 2 chars → 16^2 = 256 folders

- 100,000 / 256 = 390 files per folder. Acceptable

- 3 chars → 16^3 = 4096 folders

- 100,000 / 4096 = 24 files per folder. This creates too many directories relative to files, increasing filesystem metadata overhead without meaningful benefit.

That's why .git/objects has 256 possible directories.

Mental Model:

Phase 3 - Trees (directory snapshots)

Commands implemented:

lit write-tree: snapshot of your directory. each time you run it creates a snapshot.lit ls-tree <treeHash>: converts a tree hash back into textual content

A tree represents a directory. It contains filenames, types (blob / tree), and hashes of what they point to.

Naming conventions: We use the following digits as labels for a regular file or folder

100644 → regular file

040000 → folder (directory)

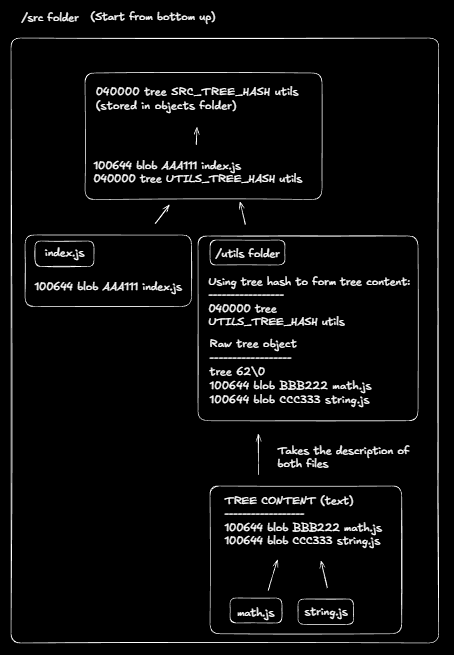

Example directory:

src/

├── index.js

├── utils/

│ ├── math.js

│ └── string.js

A folder's hash is computed from a textual description of its immediate contents. For example, the utils/ directory becomes:

100644 blob <math.js hash> math.js

100644 blob <string.js hash> string.js

This description is then converted to bytes, prefixed with tree <size>\0, hashed using SHA-1, and compressed and stored as a tree object. The resulting hash uniquely fingerprints the utils/ directory.

Once all child directories are converted into tree hashes, the parent directory (src/) can be described:

100644 blob <index.js hash> index.js

040000 tree <utils tree hash> utils

This description is processed the same way to produce the root tree hash, which represents the entire project snapshot at that moment.

That root tree hash represents the entire project snapshot at that moment.

Illustration of how it works:

Key insight

Trees do not store file contents - they store references to blobs and other trees.

Because of this:

- Any change to a file changes its blob hash

- That change propagates upward, changing parent tree hashes

- A single root tree hash uniquely represents the full directory state

This is why Git is snapshot-based, immutable, and efficient.

Phase 4 - Commits (history)

A commit never points to files. It always points to one tree.

Commands implemented

lit commit-tree <treeHash> -m "message": Given a treehash, generate a commit hash

A commit never points to files.

It always points to one tree.

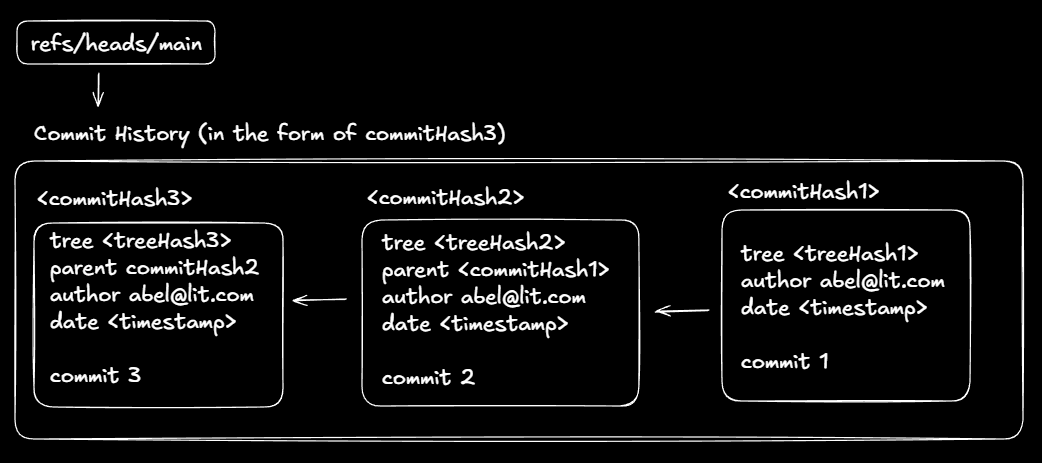

Commit anatomy

tree <treeHash>

parent <parentHash>

author <name>

date <timestamp>

commit message

What happens during commit:

- Read

.lit/HEAD→ "ref: refs/heads/main”→ tell us which branch are we on - Read

refs/heads/main→ parent commit hash OR null if its the first commit. - Create commit object

- Build commit text (the "content") based on the commit anatomy

- Move

refs/heads/mainto new commit hash (or create it if this is the first commit)

Note: A commit never points directly to files. A commit points to one tree. This is why the flow is:

write-tree →commit-tree

- generate a hash for a tree, then use that hash to generate a commit hash.

The refs/heads/main file contains the latest/current commit hash. Commit history is a linked list: commit 3 → commit 2 → commit 1

lit log

Displays the commit history starting from the current HEAD.

Example:

PS C:\Users\User\Desktop\lit\test-proj> lit log

commit 38d1a27f3fc49228286a293c45e5ded91ef6d3ed

Date: 2025-12-29T06:18:50.000Z

second commit

commit 293110c6053e18784340f51e5cb0bd460d9ff02a

Date: 2025-12-29T06:17:56.000Z

first commit

How lit log works internally:

- Read

HEADto determine the current branch - Read the branch file (e.g.

refs/heads/main) to get the latest commit hash - For each commit:

- Decompress the commit object

- Parse its textual content

- Display metadata (hash, date, message)

- Extract the

parentcommit hash

- Repeat until there is no parent

Mental Model:

HEAD

↓

refs/heads/main

↓

commit → parent → parent → parent → null

Phase 5A - Staging area (index)

Up until now, our implementation committed the working directory directly. However, Git does not commit the working directory. It commits the staging area (index).

The index defines what will be included in the next commit, regardless of what exists on disk.

lit add <file | .>

This command hashes files into blob objects and records <path> <blobHash> entries in .lit/index.

- hashes files into blob objects

- records

<path> <blobHash>entries in.lit/index

Example working directory

.

├──a.txt

└──src/

└── util.js

The index file is the staging area. It records which file paths are staged and which blob hashes they currently point to.

What the index represents

The index file is the staging area.

It records:

- which file paths are staged

- which blob hashes they currently point to

Example index file (.lit/index)

a.txt AAA111

src/util.js BBB222

Disclaimer: Real Git's index file is binary, not plain text. My simplified version uses text

This means:

a.txtis staged at blobAAA111src/util.jsis staged at blobBBB222

Key insight: The index stores files, not directories. Directories are reconstructed later during write-tree, using the staged file paths.

Step 1 - Read the index

- Read

.lit/index - If it does not exist or is empty → initialize an empty map

indexMap = {}

Step 2 - Traverse the filesystem

When running:

lit add .

Traversal order:

.

├── a.txt (file)

└── src/ (folder)

└── util.js (file)

Step 3 - Handle files

For a.txt:

- read file contents

- create blob

- compute hash →

AAA111 - update index map

indexMap = {

"a.txt" → "AAA111"

}

Step 4 - Handle folders

For src/:

- do not hash the folder

- traverse inside recursively

For src/util.js:

- create blob

- compute hash →

BBB222 - update index map

indexMap = {

"a.txt" → "AAA111",

"src/util.js" → "BBB222"

}

Step 5 - Write index to disk

The map is:

- converted to text

- sorted by path

- written to

.lit/index

a.txt AAA111

src/util.js BBB222

Key insight

The index stores files, not directories.

Directories are reconstructed later during write-tree, using the staged file paths.

Mental model

working directory

↓

lit add

↓

index (path → blob hash)

↓

write-tree

↓

tree objects

↓

commit

Phase 5B - Writing trees from the index

In earlier phases, write-tree scanned the working directory directly.

In Phase 5B, we change the approach:

Instead of scanning the filesystem, we build trees only from what is staged in the index.

High-level approach

To generate a tree hash from the index, we:

- Read

.lit/index - Build an in-memory representation of the folder structure

- Generate tree objects bottom-up

- Return the root tree hash

This ensures commits snapshot only staged files, not the entire working directory.

Core idea

- The index stores flat paths →

path → blobHash - Trees require a hierarchical structure

- Therefore, we must:

- reconstruct the directory hierarchy in memory

- hash directories only after all children are known

This mirrors how Git internally constructs trees.

Step 1 - Read the index

We read .lit/index using readIndex(), which returns a map:

indexMap = newMap([

["a.txt", "AAA111"],

["src/test.js", "BBB222"],

["src/utils/math.js", "CCC333"],

]);

Each entry represents:

<relativefilepath> →<blobhash>

Step 2 - Build an in-memory folder tree

We convert the flat paths into a nested structure.

We start with an empty root:

root = {

files: newMap(),

dirs: newMap(),

};

As we iterate through each indexed path:

- Split the path into components (e.g.

src/utils/math.js) - Walk down the directory chain, creating nodes if needed

- Insert the file into the correct directory node

Resulting structure:

root = {

files: newMap([["a.txt", "AAA111"]]),

dirs: newMap([

[

"src",

{

files: newMap([["test.js", "BBB222"]]),

dirs: newMap([

[

"utils",

{

files: newMap([["math.js", "CCC333"]]),

dirs: newMap(),

},

],

]),

},

],

]),

};

This structure now mirrors the directory hierarchy implied by the index.

Step 3 - Generate trees bottom-up

With the folder structure in place, we generate tree hashes recursively.

For each directory node:

-

Convert all files into tree entries:

100644 blob <blobHash> <fileName> -

Recursively compute hashes for child directories:

040000 tree <childTreeHash> <dirName> -

Combine these entries into a textual description

-

Prefix with

tree <size>\0 -

Hash, compress, and store the tree object

-

Return the resulting tree hash

This recursion guarantees that:

- child trees are always hashed before their parent

- the final root tree hash represents the entire staged snapshot

Summary

Phase 5B allows write-tree to operate entirely from the index.

Key outcomes:

- Commits include only staged files

- Directory structure is reconstructed in memory

- Tree hashes are generated bottom-up

- The final root tree hash uniquely represents the staged project state

This completes the transition from filesystem snapshots to index-based snapshots, aligning lit with real Git behavior.

Phase 6 - Checkout (restoring a snapshot)

lit checkout <commitHash>

Moves HEAD (and the current branch ref) to the specified commit and updates the working directory to match that snapshot.

What checkout does conceptually

Checkout restores a project snapshot by materializing a tree.

At a high level:

-

Read the commit object → extract its

tree <treeHash> -

Read the tree object → list its entries, for example:

100644 blob <blobHash> a.txt 040000 tree <treeHash> src -

For each blob:

- read the blob object

- extract raw file bytes

- write the file to disk

-

For each tree:

- recursively repeat the process inside that directory

This reconstructs the exact directory structure captured by the commit.

Safety check (blocking uncommitted changes)

Before modifying the working directory, checkout must ensure it is safe to do so.

-

Resolve the current commit:

HEAD ──► refs/heads/main ──► <commitHash> -

Read the commit object and extract its

tree <treeHash> -

Compute the current working directory tree hash (

workTree) -

Compare:

- If

workTree !== headTreeHash→ block checkout - Otherwise → checkout is safe

- If

Note: HEAD points to a branch reference (like refs/heads/main), which stores a commit hash, and the commit stores the tree hash.

The comparison is always between tree hashes, not commits.

Clearing the working directory

Once the safety check passes:

- Remove all files and folders except

.lit - The working directory is now empty and ready to be rebuilt

Recreating files from the tree

Checkout now rebuilds the project from the target commit’s tree.

Tree traversal

For each tree entry:

100644 blob BLOB_A1 a.txt

040000 tree TREE_B1 src

Blobs (files)

- Read and decompress the blob object

- Remove the header:

blob <size>\0 - Write the remaining bytes as a file

Trees (directories)

- Locate the tree object using its hash

- Decompress and parse its contents

- Recursively apply the same process to all child entries

This continues until all blobs and trees are materialized.

Updating the branch pointer

After the working directory matches the target snapshot:

- Update

refs/heads/mainto contain the checked-out commit hash HEADcontinues to point to the branch

The branch now references the newly checked-out commit.

Key insights

- Checkout restores snapshots, not deltas

- Trees describe structure; blobs describe content

- Safety checks protect the working directory

- Branches are just pointers to commits

Mental model

commit

↓

tree (snapshot)

↓

trees (folders)

↓

blobs (files)

Checkout simply reverses this structure back onto disk.

Phase 7 - lit commit

lit commit -m "message"

This command simply orchestrates existing primitives built in earlier phases.

Execution flow

- Validate input

- Ensure a commit message is provided

- Ensure HEAD is on a branch

- Read

.lit/HEAD - Block commit if in detached HEAD state

- Read

- Resolve parent commit

- Read

refs/heads/main - Use existing hash as parent (or

nullfor first commit)

- Read

- Create tree snapshot

- Read

.lit/index - Generate root tree hash (Phase 5B)

- Read

- Create commit object

- Combine tree hash, parent hash, metadata, and message

- Hash and store the commit object

- Advance branch pointer

- Update

refs/heads/mainto the new commit hash

- Update

Key takeaway

lit commit does not introduce new logic.

lit commit = write-tree (from index) + commit-tree (with that tree hash)

This mirrors how real Git builds history from simple, immutable objects.

Closing thoughts

Building lit stripped that away.

Underneath the commands are just hashes, pointers, and immutable snapshots - composed carefully to create history. Writing each piece myself forced me to understand why Git behaves the way it does, not just how to use it.

This project was my way of turning a black box into something concrete.

Related Articles

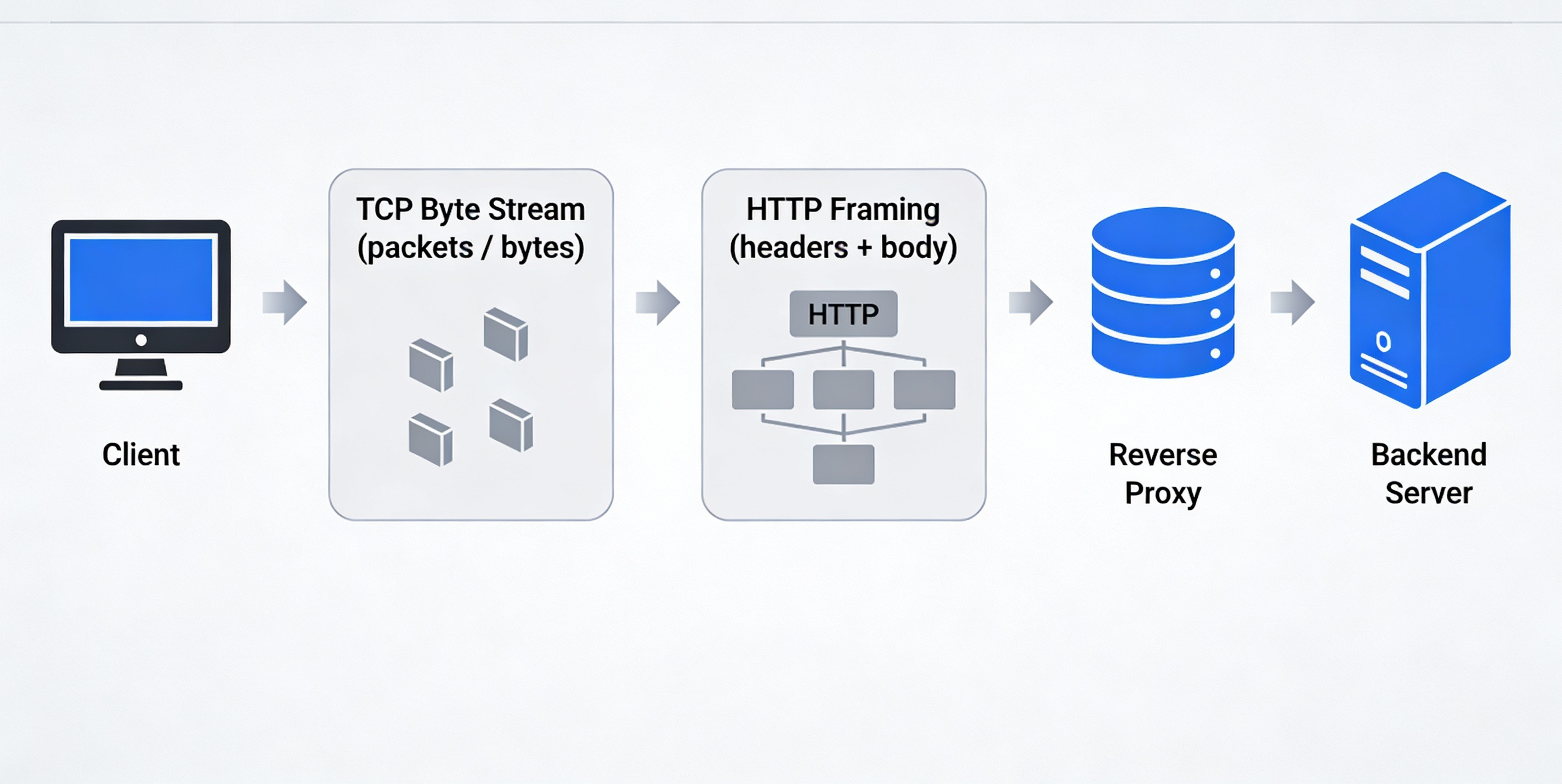

Attempting to Build an HTTP Server from Scratch (No Frameworks)

Understanding HTTP from first principles by building a minimal server and reverse proxy on raw TCP—request framing, correctness, concurrency, and guards.

I Thought Building Voice AI Was About Technology. I Was Wrong.

A reflection on building three voice AI agents at Functional AI - and how designing AI for human lives changed the way I think.